Imagine you’re a carbon molecule floating in the atmosphere and your mission is to get from there into the soil and stay there for decades.

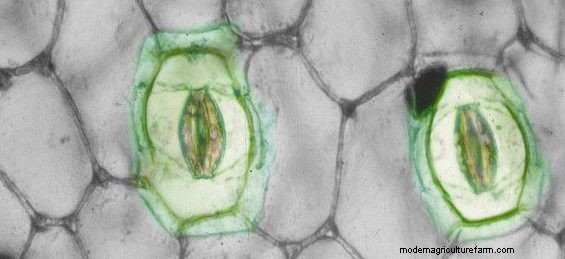

Your first step – slip into a plant through an open stoma.

Inside the plant you go through your first transformation: photosynthesis. You’re combined with water (H20) and photons from sunlight to become glucose (C6H12O6). You’re now part of the body of the plant. From here, there are multiple routes to your destination, some that take much longer than others. You could become part of the body of a cow, or part of her manure. You might be part of a plant that gets trampled onto the soil, or you might be part of the roots that get sloughed off periodically underground.

Which ever route you take, you eventually end up in the soil as organic matter – a tasty meal for soil microbes. As they eat, they respire carbon back into the atmosphere as CO2. That means that if you’re going to accomplish your mission of staying in the soil, you have to avoid these hungry microbes.

That’s the puzzle that scientists have been working on, and they’ve recently discovered how carbon molecules escape: through very tiny pore spaces in the soil.

That’s the puzzle that scientists have been working on, and they’ve recently discovered how carbon molecules escape: through very tiny pore spaces in the soil.

A team of researchers led by Alexandra Kravchenko found that the pores in the range of 30-150 µm (about the size of 1 to 3 human hairs) can trap carbon molecules, making them inaccessible to the microorganisms that might otherwise consume them and send. Of course, the more of these tiny spaces there are, the more carbon is effectively sequestered in the soil. Knowing how to create those environments will help us sequester more carbon, improving soil fertility, improving forage production and wildlife habitat, and increasing resilience to droughts and floods.

To help us with this, over a nine-year period, Alexandra Kravchenko and her team studied five cropping systems: continuous corn, corn with cover crops, a switchgrass monoculture, a poplar system with trees and undergrowth, and native succession. In the end, only the two systems with high plant diversity, poplar and native succession, resulted in higher levels of total carbon.

“What we found in native prairie, probably because of all the interactions between the roots of diverse species, is that the entire soil matrix is covered with a network of pores. Thus, the distance between the locations where the carbon input occurs, and the mineral surfaces on which it can be protected is very short,” says Kravchenko. Having these readily available escape routes means that more carbon is sequestered for the long-term.

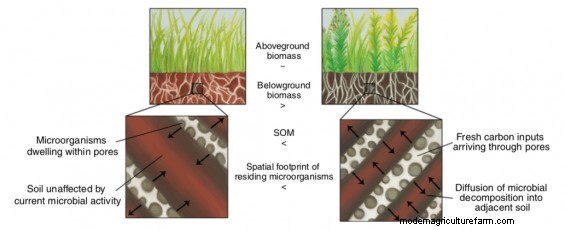

Kravchenko writes that the 30-150 µm pores are associated with the most active microorganisms that can respond rapidly to increased carbon inputs. When these pores are spread throughout the soil, as they were in the more diverse systems the team studied, the volume of the soil matrix receiving and protecting the products of microbial decomposition is greater as well, and the more soil carbon is accrued. So, while the switchgrass monoculture had the largest root mass and did create the small poor spaces necessary, there was an absence of the necessary volume of pore spaces. Once the layer next to the pore was saturated, most of the carbon was oxidized into CO2 and returned to the atmosphere.

What this tells us is that simply increasing biomass, in the form of above ground residue or below ground roots, does not necessarily help us accumulate more carbon in the soil. We now know that, not only does the plant community help determine the soil microbial community, but by adding to and changing soil pore space, they help define where microorganisms can live and how well they can function. The larger the “footprint” of the microbial community the better it is for keeping carbon in the soil.

The lesson once again is that diversity is important. If you’re looking across your pasture and see one species, think about how you might add more. Some folks have found that all it takes is better grazing management to create an environment that helps a greater variety of plants to thrive and grow. If you’re considering seeding, talk to your supplier or with Natural Resources Conservation Service, Conservation District, or Extension staff in your area about what kind of mixes will work best for you. If you’re managing row crops, use a variety of cover crops. Avoid monocultures whenever possible.

To learn even more about what Kravchenko and her team learned, download and read her journal article published in Nature Communications.