Spring is a pretty exciting time for me, as it is for all graziers. The grass bursts forth and my days are filled with watching new mothers and frolicking calves. Summer is pretty fun too, as the pastures are covered in good feed and the cattle grow fat. But even with all that glory, fall is probably my favorite time of year. Cattle drift off to market, the ranches get “put to bed” for the winter, and the afternoons take on that wonderful yellowish light that photographers love.

Oh, and hunting season begins.

Each fall I head out to the high country, looking for birds, the ones the bird books call “upland game.” The “game” here is that my buddies and I trudge up impossibly steep high-desert mountains, seeking creatures that are remarkably more suited to the country than we are. Chukar partridge run quickly up 80 degree slopes, then fly downhill at speeds approaching sixty miles per hour. Our only equalizing force is the dogs: fine Pointers with insanely tuned noses and bred-in instinct, the dogs’ job is to find birds, pin them down and wait patiently for the humans to show up. The dogs often cover 10 or 20 miles each day in rough country, while the humans scramble around trying to keep up. This is a ridiculous sport.

After a few days in Chukar camp, we often begin going for long drives in the afternoon, giving the excuse that the dogs need a rest. These treks allow us to check out new hunting spots while poking around, looking the country over and resting our own legs. Last year we were cruising across the desert, maybe twenty miles south of camp when I saw some kind of structure a half-mile to the east. As I slowed the truck down for a look, my partner asked what was up.

“Well, look out there on that flat. Looks like a set of corrals.”

“Oh boy.”

“Look, I know we’re just awful busy, but I’d like to stop and look that outfit over, if that’s alright with you.”

“Oh boy.”

A few minutes later I was standing in the load-out chute, surveying the wing fences that guide cattle into the main pen, the sorting alley, the side pens, and finally, the load-out area itself. That’s when I stopped and stared.

“Well, I’ll be danged.”

“What’s up?”

“Well, here we are, out in the middle of nowhere, and these guys have built a set of corrals with a BudBox.”

I went on to explain that the BudBox works not by forcing cattle up the chute, but by taking advantage of their normal behavior patterns and allowing them to load out quickly and quietly. I told him that using the box requires some herding skills, but was more efficient and less stressful than conventional corral designs.

“Oh boy.”

On the way back to camp I found myself thinking about that set of corrals and the BudBox. There we were, out on the desert at least fifty miles from the nearest town, looking at a set of corrals that most likely only gets used once each year, and these fellows were sophisticated enough to have a BudBox attached to their load out. Back home, I use my own shipping/receiving/processing station at least weekly through the spring and summer. Why is it that I don’t have my own BudBox? Maybe it was time for change.

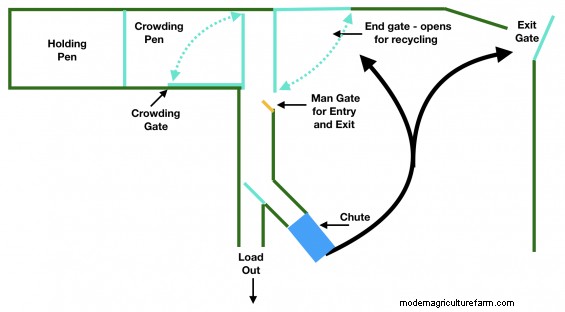

Over the past forty years or so, I’ve helped design and build several corral set-ups. Most of these are add-on affairs, taking advantage of existing structures, adding processing and load-out facilities onto loafing sheds and catch pens. Most of them look something like this:

In this situation, the herder moves a single cow or a small group of animals to the end of the pen, then uses the crowding gate to force the animals into the alley way. Some folks are more successful at this maneuver than others. For some, the crowding gate is seen as a shield that keeps the herder safe while he screams and yells and whacks at the cattle. I guess this works moderately well, but frankly, includes plenty of stress on everyone involved.

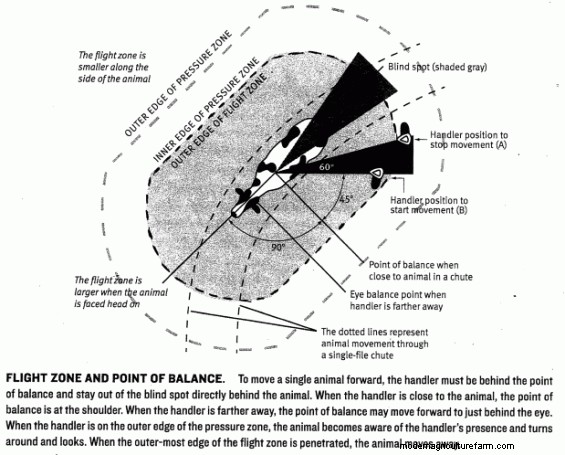

A couple decades ago we began reading about Dr. Temple Grandin’s work. She showed the importance of using angles of approach, body language, aspect and flight zones.

While her early graphics looked a bit like engineering drawings to me, as I studied and practiced her methods the results were very positive. Eventually, I found I could rely less and less on using the crowding gate as a physical force, relying instead on proper herding technique to help the cattle find the escape provided by the alleyway. The fact is, our old design worked pretty darn well, especially as our skills improved.

Still, watching videos, like the one below, of people effortlessly moving cattle from a holding pen into the working alley by using a BudBox was pretty convincing. Using a BudBox clearly requires some specific herding skill, but much less brute force.

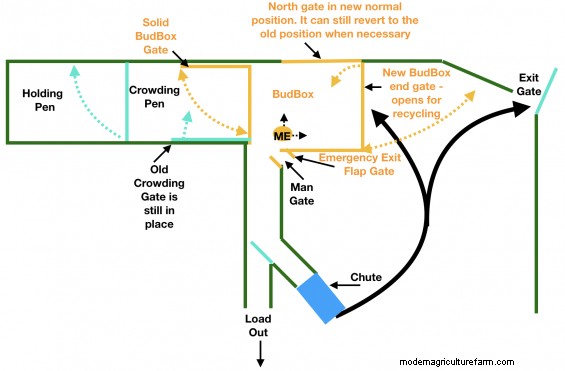

The box can also be a very modest add-on to an existing facility. All that’s required is a few panels and some re-design work. After seeing that BudBox out on the desert, I guess I felt compelled to build my own.

Last spring, I opened the end gate at my main processing center and added a few panels, constructing a crude BudBox. Throughout the season I tinkered with the box, moving the panels to change width, depth, and angles. Throughout the season I learned a bit and improved my herding skills. In the end, I settled on a design that looks like this. You can see the changes I made in yellow/orange:

And here it is from the cow’s eye view:

For the first time in many, many years, we have exactly zero cows staying with us this winter, so I’m a bit short on animals to practice with. I do happen to have a couple of young bulls hanging around the HQ, so I put them through the new Bud Box several times. The results were about as expected: extremely easy, quiet, calm, with those boys walking slowly up the alley toward the working chute. I find myself looking forward to some new arrivals, cows that have never seen a Bud Box before. All a-tingle, here.

I’m all set for a calm and easy winter here, looking forward to a great spring with plenty of…

Happy Grazing!

Stay tuned! John will be sharing more on this topic. He’s got some great information on designing processing facilities for a single herdsman. He’ll also be talking about the thinking involved in looking at an existing set up and figuring out how to convert it to a better BudBox system.