After hearing about keyline plowing from advocates in Vermont, farmers wanted to know more. They wanted to know if it truly could reduce compaction, build soil and increase carbon sequestration. Four Vermont dairy farmers offered their farms as sites to test the plowing system, and we began a three-year research project, working with Mark Krawczyk of Keyline Vermont, a trained keyline expert.

Our intent was to use the tool as prescribed and then to gather data to tell us what kind of changes could be expected from the practice. To make sure that the data we collected would be useful, we wanted a variety of pastures and similar untreated pastures for comparison. The pastures chosen for treatment were selected by the farmers because they were in need of improvement. The farmers had plans to completely rehabilitate those pastures but were interested in trying keyline plowing as an alternative.

Mark Krawczyk of Keyline Vermont owns a Yeoman’s plow and knows how to keyline plow. He came out and found the keypoint for each paddock, plotting the keyline with temporary flags. Hitching his 3-shank plow to the farmer’s tractor, he plowed the paddock to about 10-14” depth for the first pass at the beginning of the grazing season. Later that summer, he plowed a few inches deeper. The third and fourth passes were completed in the second year. By the fourth plowing, the shanks were at their fullest extension, reaching depths of 20” or more.

Before and throughout the process, the dairy farmers maintained their grazing management. For three of the four farmers, herds of dairy cows or heifers grazed for 12 to 24 hours on the pasture, and farmers were careful to avoid overgrazing. The fourth farmer used longer grazing periods, and often used both control and plowed pasture space to support his heifers. [Note: this is a correction from the previous statement of 4 farmers all using similar management.] The herds were brought into the paddocks when forages were at about 8-12” and came off before the forage reached 3-4”.

A team of us from the University of Vermont, including soil scientist Josef Gorres, myself and graduate student Bridgett Hilshey, collected soil and forage samples from the keyline plowed pastures and from the neighboring comparison pastures before during and after the two years of the project. For good measure, we also tested penetrometer resistance and rated the pastures’ conditions. For each soil sample, we did a basic soil test, and measured organic matter content, soil strength, bulk density, linear porosity and active carbon.

One of the key things that farmers were interested in improving with this treatment was compaction. All four farmers felt their pastures were lagging in productivity and quality, primarily because of compaction, and while they were still functional, the farmers wanted to rejuvenate them.

Soils can get compacted from machinery traffic and from animal traffic. The hooves of animals can force a lot of pressure on those upper 4-6 inches of soil. If animals are out grazing when the soil is wet, compaction is even more likely. Some studies have found pasture yields can be 16-40% lower as a result of compaction. Keyline plowing was ideal because it was said to alleviate compaction, increase pasture yields, and it wouldn’t interfere with grazing management. Since the plowing doesn’t disturb the pasture measurably, the herd could go back to grazing soon after each plowing event

Even though originally, we were trying to address soil compaction, active carbon was the key characteristic for us to watch. It responds quickly to management changes, because active carbon is tied to changes in biological activity, meaning that if there is much more food available for soil microbes, there would be more active carbon present. If changes were afoot, we should see it in active carbon measurements.

Out of the hundreds of samples, and readings, and measurements, we saw no changes. No changes to the very responsive indicator, active carbon, and no changes in other soil or forage characteristics, such as soil organic matter or bulk density, or forage NDF. What this trial told us is: keyline plowing didn’t change soil or forage quality on these four farms over the 2 ½ years we were monitoring pastures. There may be additional conclusions to draw, but first let’s talk with the farmers.

The farmers told us some more. They were pretty frustrated by what keyline plowing did- three of the four said it made those paddocks very bumpy to walk across. For the ones that hayed or mowed pastures in addition to grazing them, they said that the tractor ride was very uncomfortable. The shanks of the plow pulled up stones, and that was really irritating. Mark added a roller behind the plow to smooth the surface, but the slices still made the pastures a pain in the tush.

A couple of the farmers were dealing with moisture issues in their pastures. In one case, the farmer noted that it seemed like the plow lines were moving water away from wet spots, and that was appreciated. In another case, though, the farmer said it seemed like the plowing dried the pasture out more rapidly, and the plants looked like they were drought stressed.

There was another group we still wanted to hear from. Earthworms are pretty good indicators of soil quality, and we were counting on them to shed more light on the situation.

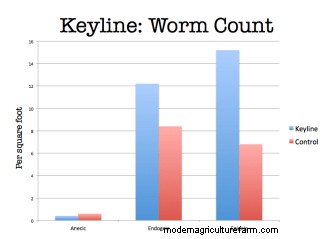

There are three main types of worms: Endogeic, epigeic, and anecic. The endogeic and the epigeic stay closer to the surface. The anecic, though, burrow deep into the ground. Those deep burrows can translate into lost nutrients, when the materials the anecic worms have transported are washed deep into the soil profile, sometimes reaching the groundwater. The worm counts told a story that we didn’t find anywhere else. We found higher numbers of endogeic and epigeic worms in the keyline plowed pastures than in the control. The numbers of anecic worms were not that different though.

There was an average of 27 endogeic and epigeic worms per square foot in the keyline plowed pastures, versus the 15 per square foot in the control. An acre has 43,560 square feet. With an extra 12 worms per square foot, there were 522,720 more worms per acre in the keyline-plowed pastures. The presence of more worms suggests faster turnover of nutrients and better aeration.

The cost of keyline plowing was about $280/acre, or about 1867 worms for every dollar. Since we didn’t find any increase in forage, forage quality or other soil quality indicators, we’re left wondering if opening up the soil to more worms is worth it. More worms has usually been considered a good thing, and at almost 20 worms for a penny, those worms seem like a great price.

It turns out that worms might not be the best things for climate change, though. The process of churning and digesting organic matter seems to increase the release of greenhouse gases and doesn’t seem to increase the amount of carbon being stored in the soil.

With the verdict on worms not 100% positive (sorry, worms, we really do love you!), we’re still asking, what will we see in the long run? We haven’t seen the 8” of topsoil that was touted, with no increase in organic matter or active carbon. Since we burned a good bit of diesel for those worms, we definitely didn’t do the environment any favors.

Is it that keyline plowing is more suited for drier climates, where water is a limiting factor in production? We’re still working on that answer, and we’ll get back to you. Keyline plowing has been out there for decades, though, so if you have any evidence or data, please share it!

Until then, it’s hot out. Let’s dig up some worms and go fishing.