Thanks to Randy Comeleo, Program Advisor for the Agriculture and Wildlife Protection Program, Benton County, Oregon, for helping with this article.

Last week’s article, “Coyotes Can Protect Your Livestock From Predators” reviewed some the research showing that we may be better off not killing predators. In fact, researchers found that the more predators we remove, the more livestock are killed. Based on this, they believe that properly implemented non-lethal predator control could considerably reduce the need for lethal control.

It was this scientific information, along with actual numbers comparing the cost of killing and trapping with the losses producers suffered, that led local farming and wildlife conservation leaders in Benton County, Oregon, to develop a non-lethal deterrents grant program as an alternative to the county trapping program.

USDA and county reports showed that, from 2004 to 2014, the county lethal control program had cost county residents $174,590, while residents sustained $166,406 in agricultural and property losses. During this ten year period, livestock killed by wildlife included 456 sheep, 393 fowl, and 43 goats. In response, USDA government trappers killed 738 mammals, including 456 coyotes, 50 raccoons, and 46 bobcats using neck snares, steel-jawed leghold, and body-gripping traps.

At workshops and farm visits during development of the grant program proposal, farmers said they were (1) weary of reacting to livestock losses after they had already occurred, (2) found lethal methods did not work or provide long-term protection, (3) were uncomfortable killing native wildlife in an attempt to protect their livestock, and (4) received no support for using proactive non-lethal methods from the county lethal control program. One of the most common reasons cited by farmers for wanting to use non-lethal deterrents was that they believed wildlife played an important ecological role in the health of their farm ecosystem.

In June 2017, the Benton County Budget Committee approved a two-year pilot program to encourage the proactive use of non-lethal animal damage deterrents in an effort to foster the coexistence of agriculture and wildlife. Benton County farmers and ranchers could apply for cost-share reimbursement for implementing non-lethal predator control through the Agriculture and Wildlife Protection Program (AWPP). Education and consultation services are provided by Oregon State University Extension Service, Chintimini Wildlife Center, and program advisors with expertise in ranching with wildlife, predator ecology, and human-carnivore conflict.

The results of the two-year pilot program were quite positive as described in excerpts from the 2017-2019 AWPP Summary Report. Grant recipients were required to maintain detailed records of their non-lethal deterrents project operations and submit an annual report evaluating the effectiveness of the non-lethal methods and tools used. The AWPP Summary Report is based on these project reports:

These results are consistent with what other farmers and ranchers have reported about their own non-lethal programs. In Benton County, the early success of the non-lethal deterrents grant program led the Budget Committee to approve $45,000 to continue the program in the 2019-2021 biennium.

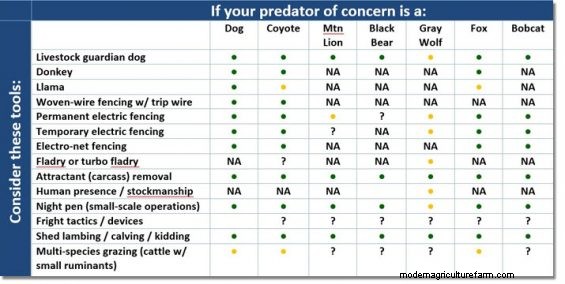

The Predator Hub of UC Rangelands at the University of California, Davis has collected a lot of information we can use to determine what will work best for our individual operations. This table gives you a feel for what they cover:

We summarized their findings in this June 2018 On Pasture article.

We’ve got some other predator control methods to share as well. So stay tuned for more!