In southwestern Kansas, where the lack of rain has become a persistent problem, farmers rely on irrigation to feed thirsty crops. They pull water from the Ogallala Aquifer, but the ancient underground aquifer is drying up – the water table is dropping by as much as 2 feet per year in some counties.

“If we’re taking 12 inches out of the ground in a normal year in this region on average, we’re only getting a ¼-inch recharge,” says Tracy Streeter, director of the Kansas Water Office. “We’re in a mining situation, and it is why it’s so critical we slow down that rate of decline.”

A recent four-year study by Kansas State University projected that if the existing trends continue, nearly 70% of the Ogallala will be depleted by 2060. Once depleted, the study says, depending on the district, it will take 500 to 1,300 years to refill naturally.

This ominous news not only threatens a way of life generations of farmers have worked so hard to build, but also jeopardizes the very existence of communities like Garden City whose economy is driven largely by agriculture. Yet, this latest revelation is not surprising to anyone, because the state has been talking about how to mitigate this dwindling resource for decades.

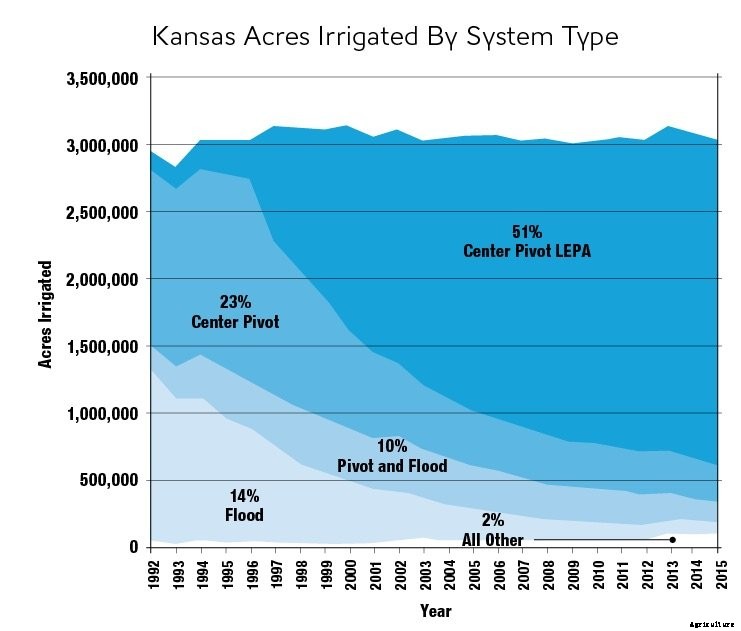

“We have had a number of strategies over the last several decades to try to slow down the rate of decline in this aquifer,” says Streeter. “We needed to come up with a strategy that not only reduces pumping through volume reduction programs but also uses technology to maintain that economic return with less water use.”

Through the state’s water vision, the Kansas Water Office is teaming up with forward-looking farmers to develop Water Technology Farms. The concept emerged as an action item within the vision, which Governor Sam Brownback called for in 2013 to address the state’s water supply issues. The farms are designed to demonstrate the effectiveness of the latest technology in irrigation water management without sacrificing yield.

“This is critical if we’re going to increase confidence and spur adoption by irrigators,” says Streeter, who was appointed to lead the water vision team.

Owned by Tom Willis, T&O Farms, LLC, is the first and largest farm in the three-year program, which began in 2016. His motivation for participating is twofold.

Not only does Willis grow alfalfa, wheat, sorghum, corn, and soybeans near Garden City, but also he is the CEO of Conestoga Energy Partners. The company owns two ethanol plants in Kansas that depend on local corn and sorghum for production.

“I’ve had to redrill two wells in the last three years,” he says. “I can’t afford to have these wells go dry, because I’ll be forced to import grain and compete in a larger marketplace.”

Willis also has a son who recently returned to the farm. “Josh was an Army captain and came back to the farm last fall,” he says. “I also have a new grandson. My goal is to have this farm in our family for generations to come. That’s extremely important to me, because I want that legacy for my family.”

In order to be sustainable for the long term, he is willing to implement a water-reduction plan.

“I have 1,250 irrigated acres under 10 center pivots,” Willis says. “I’m allocated 2,270 acre-feet of water that I can pump a year, which is not sustainable in this part of the Ogallala. I know there is risk that comes with using less water. By being a part of this project, I want to prove that I can save water and not sacrifice yields.”

Working with Mike Meyer, water commissioner for the Division of Water Resources in Garden City, Willis has voluntarily taken a 33% cut in water use.

“In 2015, I was pumping 425 gallons per minute on one field. I only pumped 375 gallons per minute on that same field in 2016,” says Willis. “I’ve applied that 50-gallon-per-minute cut across the eight fields I’m experimenting on.”

By the end of the program, he wants to drop his water use even more.

“If I can get to a 50% reduction by 2018 and still grow the same size crop I’m growing today or make the same bottom-line profit I’m making today, my goal is to make that 50% reduction permanent,” says Willis. “If I can cut my water use by 50%, I think the life of this aquifer can be extended another 30 to 35 years.”

Willis says a successful water-reduction plan revolves around six key actions.

1. Invest in technology. “To be able to pump less water, I had to incorporate the Dragon-Line system,” he says.

The eight fields in the project are a paired study and grow the same crop. Four of the center pivots are equipped with Dragon-Line and four use low-pressure spray nozzles.

“I developed a process to uniformly take precision mobile drip irrigation and marry it to a center pivot, which is more flexible to use than drip irrigation alone,” says Monty Teeter, CEO of Teeter Irrigation.

The orange drip-line tubing has a 1-gallon-per-hour pressure compensating emitter every 6 inches. An emitter is fully operational at 7 psi and is self-flushing. The drip-line tubing is then attached to the Dragon Flex Hose, which drags on the soil surface.

“As Dragon-Line is pulled behind the system, the emitters deliver a uniform water pattern across the full length of the irrigated area,” Teeter says. “It significantly reduces soil water evaporation and eliminates wind drift if the drip is kept on the ground.”

The Dragon-Line, he adds, costs between $100 and $250 per acre. It costs about 10% of a typical automated subsurface drip irrigation system and is expected to exceed 12 to 15 years of useful life.

2. Install soil moisture probes. “The second piece is knowing what is going on underneath the ground, because it tells an important story,” says Willis.

Two soil moisture probes were installed in each field and go down 42 inches.

“The probes give a reading every 30 minutes as to what is going on in terms of root development, evaporative transfer, water storage, and how much penetration I'm getting down in the ground,” he explains. “I can access that information on my smartphone.”

That data has been invaluable in determining how thirsty crops truly are.

“I have one circle of corn I turned off last Monday, and I am done watering it for the season,” Willis says. “Normally, I would have watered that another 20 days, but those probes are telling me the crop doesn’t need any more water. That’s two and one-half weeks of water savings that I didn’t take last year.”

3. Watch weather. A weather station was donated by Kansas State University. Willis is working with researchers at the university and also with Loren Seaman of Seaman Crop Consulting in Hugoton, Kansas, to measure the weather variances.

4. Install an index well. The Kansas Geological Survey has installed an index well to measure real-time data. The index well program is a pilot study of an improved approach to measure the water level and quality of water at the local level.

5. Rotate crops. Willis is planting a rotation of crops including corn, sorghum, soybeans, and alfalfa. His plan is to reduce the acres of corn he plants and increase the acres of crops that require less water. While he won’t stop planting corn completely, he does plan to utilize a shorter-season variety.

6. Monitor progress. The systems are fully automated with water use and groundwater levels and are tied to a real-time website so others can see how the project is going. Seaman and Kansas State Research and Extension are lending their expertise to report the findings.

Visit the Kansas Water Office at kwo.org.

Below is an example of Tom Willis’ center pivots across five section tracts of land that draw from the Ogallala Aquifer. The scenario of one of these section tracts of land shows the implications of what would happen with and without water reductions.

Producers were encountering mobile drip irrigation (MDI) and were asking us what we knew about it,” says Isaya Kisekka, Kansas State University.

At the time, the university didn’t have any experiments on MDI, so it initiated a study in 2015 to answer these questions:

“Through our involvement in the Water Technology Farms and our research at the Southwest Research - Extension Center in Garden City, we will be able to demonstrate what we have learned so far,” Kisekka says.

Year one revealed that there were some advantages to MDI.

“We were able to measure 27% to 35% less soil water evaporation than we would normally see with a spray nozzle,” says Jonathan Aguilar, Kansas State Research and Extension. “Translated to the whole season, it could be about 3 inches of water for the entire crop.”

Researchers were also surprised by the moisture in the soil after harvest. “There was a lot more soil water under mobile drip irrigation compared with fields that utilized a spray nozzle. We associated that with less soil water evaporation we saw,” Aguilar concludes.

The Dragon-Line system combines the efficiency of mobile drip irrigation (MDI) with the flexibility and economics of mechanized irrigation systems. Its creator, Monty Teeter of Teeter Irrigation, shares six key benefits of the system.