Conceived by Tony Allan, virtual water trade, also referred to as the trade of embodied or embedded water, revolves around the idea of virtual water exchange whenever goods or services are traded. The recent trade war between China and the United States since 2018 was chiefly about virtual water or the hidden water in products.

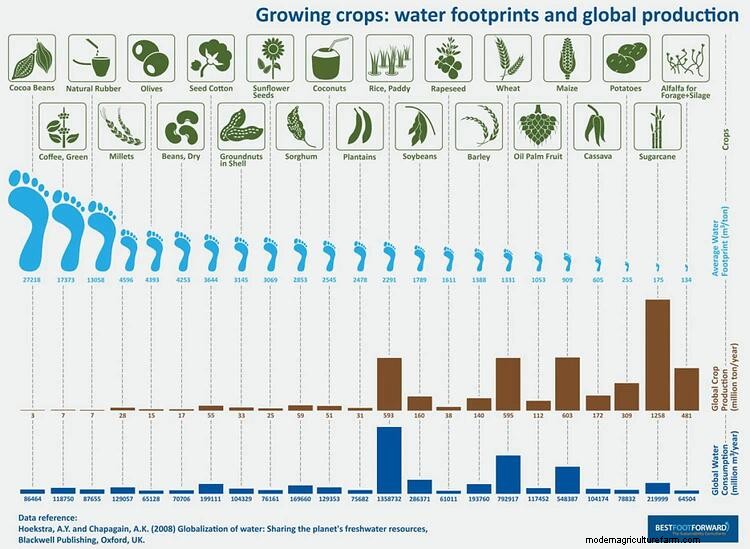

The production of any agricultural commodity requires water, and therefore, has a significant water footprint. Add to that the cost of packaging, shipping, and trading after production, which further adds to the hidden water cost. Speaking particularly about India, it is, historically, the net exporter of virtual water due to its sizeable agricultural exports .

So, what is virtual water, and what is its importance and impact on the global scale? Keep reading to know more.

The concept of virtual water is more important now than ever since it helps realize the illusion of food security and water, despite sufficient evidence that there are inadequate water resources to sustain national economies.

Virtual water refers to the water contained in fiber, food (any agricultural product), and non-food commodities such as energy.

Let us understand what is virtual water with the help of a simple example:

Consider that to produce one ton of wheat, close to 1,300 cubic meters of water is required. When a country imports this tonne of wheat grains, it can use the existing indigenous water it saves for other purposes instead. However, if the exporting country is water-scarce, the shipped virtual water will be no longer available for other purposes.

Similarly, about 16,000 tons of water are essential to produce a ton of beef. Therefore, someone consuming beef often is likely to absorb substantially more water than someone on a vegetarian diet.

Several nations strategically conserve their domestic water resources by importing water-intensive products and, in return, exporting relatively less water-intensive commodities. Some others also discourage the export of certain goods, such as oranges in Israel.

Simply put, the concept of virtual water helps us understand:

Now, this is where the importance of the virtual water trade comes into the picture.

Virtual water trade exactly means what the name implies – the import and export of ‘hidden’ water present in various products, such as textiles, machinery, livestock, and crops. All these require water inevitably for their production.

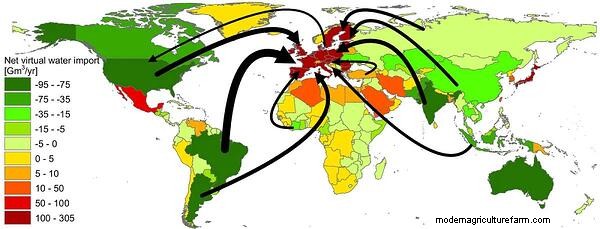

Virtual water trade is now a globally relevant topic, especially when nations are struggling with the consequences of climate change. China, historically, has been a net importer of virtual water. On the other hand, India’s exports are highly water-intensive due to its large variety of agricultural exports. As a result, it puts water sustainability at significant risk.

Virtual water imports into Europe.

Source: Virtual Water Trade , Water Footprint Network

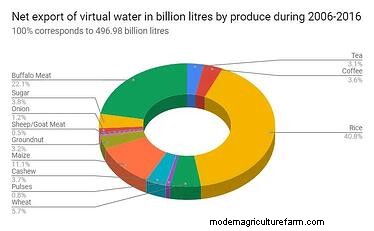

According to a study published in the Groundwater for Sustainable Development for 2006-2016, India exported nearly 26,000 million liters of virtual water every year. The most exported products were rice, buffalo meat, and maize.

In a nutshell, India’s net imported virtual water during this period was 237.21 trillion liters, while exported virtual water was close to 500 trillion litrers.

Source: “Trading in virtual water: Time to rethink India’s exports?”, Research Matters

Discussed below are some more detailed examples of virtual water trade:

Virtual water trade can act as an ideal alternative to inter-basin water transfers between or within countries. Case in point, China is considering several water transfer schemes from north to south. Virtual water trade can also serve as an eco-friendly and more sustainable alternative to water transfer schemes in South African nations. Therefore, this trade can significantly influence the management of international river basins, thereby influencing agriculture in the long run.

Virtual water trade can seriously affect water management practices in regions or nations prone to water scarcity issues. For instance, the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana, two of the most water-stressed zones in the country, demonstrate unsustainable patterns of water usage for the production of water-intensive food grains, and its subsequent trade to other water-stressed or water-rich regions. A recent study is also urging shifting the majority of rice production to central and eastern states of India while promoting sustainable wheat cultivation instead in the above-mentioned rice-growing regions, to help the country mitigate the impending water crisis.

Discussed below are some of the main benefits of the virtual water trade.

However, while talking about what is virtual water trade, one cannot overlook its cons.

Global per-capita food consumption has grown faster than the population in the last two decades due to income growth and changes in consumer preferences. Meanwhile, the availability and quality of land and water resources for agriculture are deteriorating.

While we may only be barely conscious of the water that a beverage or item contains, there is more ‘invisible’ water that we fail to consider. Notably, producing food consumes more water than any other economic or social activity. The water footprint for these products includes the large volumes of water used throughout the product’s journey to the consumer.

For instance, you may use only about a cup of water for your morning coffee. Yet, it consumes 140 liters of water to produce, package, and ship the coffee beans to your nearest store, which is nearly the same amount that an average person in England needs for their daily drinking and household needs.

At an individual level, the recent consumer behavior changes that spur sustainability, such as reduced meat consumption and a shift to a plant-based diet, are creating a new target segment now known as the ‘green consumer’.

In today’s hyper-connected world, social influence is a significant driving factor that affects the consumers’ consumption process. Effectively, consumers voluntarily reduce or simplify their consumption, to begin with; opt for products with sustainable sourcing, production, and other features; actively conserve energy, water, and products during use; and adopt more sustainable product disposal methods.

This consumer behavior, in turn, affects the environmental and sustainability performance of local and international brands. The more ‘aware’ consumers want more than sustainable products – they want the companies they support to be sustainable in their corporate operations, too.

If the water footprint varies from one country to another, you will automatically ask if virtual water is fair and sustainable or not. If we talk about the Northern industrial nations, the virtual water consumption is significantly higher due to the abundance of water resources. Besides, it signifies a robust purchasing power and the need for water-intensive products. It is here that the dilemma arises. For a fair virtual water trade, the worldwide maximum sustainable water footprint should be divided equally among all the nations.

Now, water-rich countries like the USA have no reason to consume more water than required, and hence, they deal in exports. It automatically means that the countries it is exporting to develop dependencies soon, thereby creating an imbalance.

Some of the best practices in this regard are listed below: