Troy started this piece, Kathy Voth added some, and Jim Gerrish shared his observations. And with all that, we’re still not sure we have an answer.

The heifers moved ahead into a fresh break of pasture while I lingered and admired the trample effect that was left behind. The rough residual was a beautiful combination of chomped grass, top-grazed forbs and a twisted bed of tall, old-man grass folded down like a blanket, upon the soil by the hoof action.

It was so perfect, no further action was needed. So I lingered a bit to consider this question: “Does grazed, and or, trampled forage grow back faster than mechanically cut pasture?”

It’s a discussion that’s long in the tooth around these parts and comes up when the pastures get out of hand and we feel compelled to do something about it. It’s also what a group of Sterling College students in Vermont asked me to explain at a workshop I was leading for them: “Why is grazing and trampling better? And why would trampled grass grow back faster than if you simply clipped it with a mower?”

Not surprisingly, I found myself in a B.S. position. Drawing from my experience listening to famous holistic, mob-grazing practitioners, and believing them, I just said it was so, with only anecdotes for real proof. As I looked at their confusion over how a pile of trampled thatch could regrow quicker than a clean-cut grass clump with full sun, I too, started to question the hypothesis. Adding to my confusion – I have just as many grazing friends who swear that a sharp blade of a disc-bine or sicklebar mower helps the grass grow faster. And then there are us “Bush-hoggers” who shred their plants. That couldn’t possibly be contributing to higher growth rates, could it?

No doubt the mechanical side of things can keep a sward more uniform and vegetative while removing competition from undesirable species. In fast growth times this pruning can be an effective tool for increased dry matter. But is it fundamentally better than a grazing animal? Where is the research that says its better?

I consulted the internet for a scientific answer – where I literally found spit on the topic!

Yes! There are researchers who study animals’ magical saliva to see if the PH, thiamine, and dripping rumen bug juice contribute to increased plant growth and tillering rates. So let’s turn it over to Kathy who gathered some of the literature on this.

Scientists were inspired to study the effect of saliva on plant growth because it contains thiamine in concentrations strong enough to potentially stimulate growth. Results of their research have been mixed.

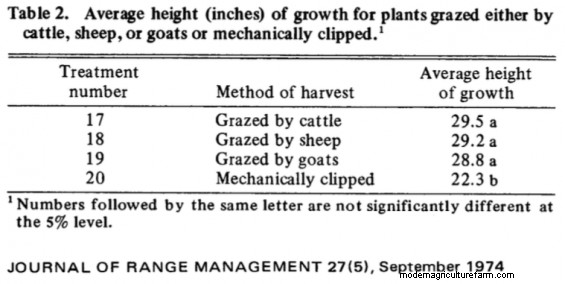

A table in a 1974, 2-page Journal of Range Management “Technical Note” by Reardon, Leinweber and Merrill seems to be the source of the idea that saliva can increase growth by 30%. The methods explanation is a bit unclear, but it appears the authors compared the growth of 15 seedlings grazed by either cows, goats and sheep with plants that they clipped to the same grazed height, resulting in this table:

But when they tested growth due to saliva applied to clipped plants, or to thiamine on clipped plants or on the soil, they found no significant changes.

A study of the effect of bison saliva on blue grama showed no benefit from saliva. Likewise, Canadian scientists found cow saliva had no effect on Altai/rough fescue or Idaho fescue. And a 1986 analysis of the research on this topic found that strong evidence was lacking and that strong growth only occurred in growth-chamber conditions.

On the other hand, a more recent study of sheep saliva on Chinese ryegrass found an increase in tillering and changes to carbohydrate storage in the plant. (This paper had a great description of the methods the researchers used including that they gathered sheep saliva by having sheep chew on a sponge, and then squeezing the sponge out into a tube.) A test of goat saliva on Red Bushwillow in Botswana showed that saliva treated shoots grew much more than untreated shoots, but unclipped shoots grew the most.

While this all leaves us up in the air as to the impact of saliva on plants, many of the papers I read came to the same conclusion: The shorter you graze or clip a plant, the more slowly it grows back, even if you give it lots of rest. Grazing or clipping longer always had better results, thus reinforcing a lesson we’ve all been taught over and over.

With no good answer, I wrote to Jim Gerrish who has a lot of experience running studies, reading research papers, and doing good grazing on the ground. Here’s what he had to add to the discussion.

I think the research of recovery rate with trampling and cow spit is very nebulous because there are so many attenuating circumstances that affect how a pasture is going to recover following perturbation. Thus, I have little confidence in the limited research out there.

Here is my own experience:

I consistently see better regrowth following proper grazing compared to following the mower. Because the pasture sward is uneven when we begin grazing, I expect to see an uneven residual. If we leave a proper amount of leaf area on each of the species in the mixture, because the stock took a bite off of everything, we generally see a uniform and rapid recovery.

Following mowing, particularly a close mowing as most mechanical mowers or conditioners leave, the plants most tolerant of close clipping recover while the species requiring taller residuals (more leaf surface) suffer. Thus, we have more limited recovery following mowing.

Regarding cow saliva, because I do believe in co-evolution of grassland and ruminants, I have to believe there is a metabolic relationship. Does cow spit give us 30 to 44% increases in productivity? I am yet to be convinced.

In my experience, I see more rapid recovery on what I describe as a standing residual as opposed to trampled residual. Here’s a picture of what I mean by standing residual.

And here’s what I mean by trampled residual.

I generally see 10-20 day added recovery time to grow a ton of new feed from a trampled residual compared to standing residual. That is on irrigated land.

We are all products of our own experiences.

About the time we were all thinking about this, I showed a group of farmers a picture of a June clipped pasture versus grazed and trampled on the other side of the break wire. 100% said they liked the look of the clipped pasture better. But by August the trampled sward was producing twice as much dry matter per acre. Why?

If you went by strictly growth rates, the clipped one got a good jump of forage but the trample slowly fed the biology and covered the soil allowing more diversity and soil life action that accumulated more mass as dry weather ensued. I equate this phenomenon to compensatory gain in cattle. Unfortunately this was not proven by science either way, so I too, practice anecdotes.

Back at our farm, a side by side farm-based trial is underway as my dad clipped the heavy grazing residual next to the trampled animal impact paddock.

With little rain and now 30 days of recovery, the two paddocks are running neck and neck.

But there is one glaring distinction that should weigh on everyone’s mind before you hook up an expensive piece of iron to manicure a farm. The temperature of the soil surface on the trampled paddock is 20 degrees cooler and when it rains a tenth or we just have a heavy dew, the paddock retains moisture longer.

I feel our farm’s resiliency is the measure of water retention practices like grazing right for the right reasons. I’m not sure if clipping achieves such a solution.

What are your thoughts or contributions? Do you have some scientific literature to add to the mix? Let’s discuss in the comments below!