Watching little green tomatoes mature into large ripe tomatoes is one of the garden’s greatest joys. But when something goes awry and those ripe red fruits don’t come to fruition, it can be heartbreaking. Though tomatoes are subject to several different fungal diseases that can affect fruit development, perhaps the most upsetting tomato disorder of all is blossom end rot. Thankfully, if you can properly ID this disorder and learn to prevent and treat it, you won’t have to face the heartbreak it brings in future years.

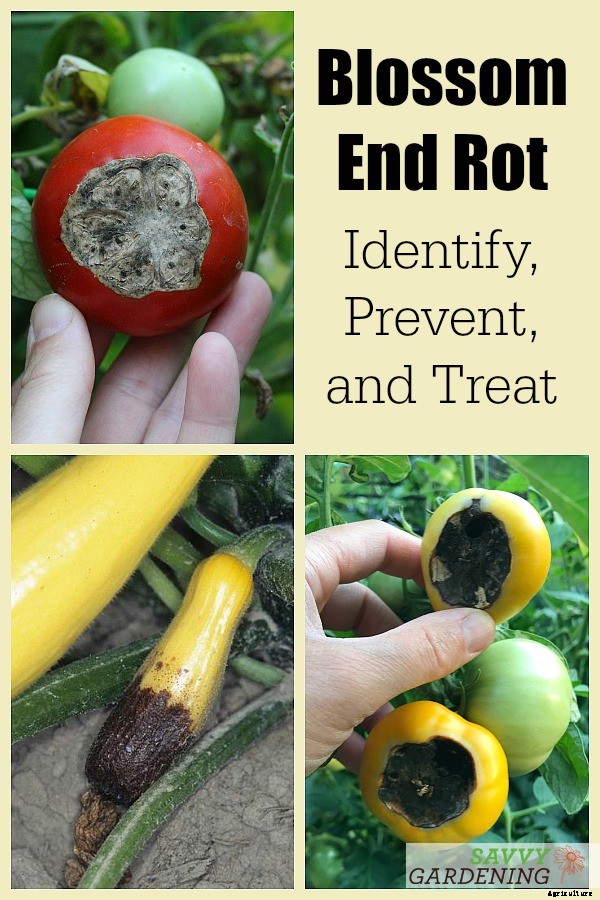

Gardeners who experience blossom end rot will not soon forget it. The distinctive appearance of affected fruits is pretty memorable. Blackened, sunken cankers appear on the bottom (blossom end) of the fruits. The top of the tomatoes look completely normal, but when the gardener plucks them from the vine and turns them over, the black lesion is clearly evident on the bottom of the fruit.

Blossom end rot appears most often as a single canker that starts out small and grows over time, but occasionally you may see two or three lesions instead. They are always on the blossom end of the fruits, never on the top. Though this disorder occurs most often on tomatoes, several other vegetables are susceptible too, including peppers, summer squash, and cucumbers.

Before we tackle how to prevent and fix this troublesome issue, it’s important to understand why your plants develop it in the first place.

Though many people think blossom end rot is a disease, it isn’t. Blossom end rot is not caused by a bacteria or fungus, nor is it something that is caused by an insect pest. It is a physiological disorder thought to be caused by stress combined with a lack of calcium in the developing fruit (though one study, highlighted here, has examined anther possible reason).

During the gardening season, tomatoes develop at a very rapid rate, and they use a lot of calcium in the growing process. When there is not enough calcium present in the plant, the fruit’s tissue breaks down into the sunken lesion you see at the bottom. The blossom end of the fruit is its growing point, so that’s why the deficiency symptoms show up there first.

This lack of calcium can be caused by a few different things. First, there may be a deficiency of calcium in your soil, though this is fairly rare in most garden soils. A soil test will tell you if your soil is deficient in calcium, but again, this is not the most common culprit. The most common reason for a lack of calcium in the developing fruit is actually a lack of consistent soil moisture. Let me explain.

Unlike some other nutrients which come into a plant’s roots through diffusion, calcium is acquired by a plant primarily through a process called mass flow. Mass flow occurs when water carries a dissolved nutrient into the root of a plant. This means that calcium primarily comes into the plant via the water absorbed by the roots. If there isn’t enough water coming into the plant, it can’t get the calcium it needs, even if there’s plenty of calcium in the soil. As a result, the plant begins to show signs of a calcium deficiency.

As I mentioned before, soil calcium deficiencies are unusual in a garden setting. The calcium is likely in the soil; your plants just can’t access it unless they have ample and consistent water. The same goes for plants grown in pots, especially if they’re grown in a commercial potting soil with added fertilizer or potting soil mixed with compost. The calcium is there; your plants just aren’t getting it. Blossom end rot is especially common in container-grown tomatoes or during years of inconsistent rainfall.

When vegetable plants are subjected to dry periods, the calcium cannot move into the fruits where it’s needed for proper growth. This leads to a calcium deficiency and blossom end rot. Here’s what different vegetables look like with blossom end rot.

Thankfully, blossom-end rot is preventable. Consistent soil moisture is the key to preventing this disorder. Be sure to regularly water your tomatoes during periods of dry weather. They need around one inch of water per week, and it’s much better to apply that full amount of water all at once via a slow, steady soak to the root zone. Applying a little water every day or every few days only makes the problem worse because the water doesn’t penetrate down into the soil to saturate the entire root zone. Keep in mind that the calcium in your soil isn’t always right next to the plant’s roots – it may have to travel some distance to enter the plant with soil moisture.

Aside from watering consistently and properly, here are a few other things you can do to prevent blossom end rot.

As I mentioned earlier, blossom end rot is particularly problematic when growing in containers because they are often left to dry out in between waterings. Or, they aren’t watered as deeply as they should be. Here are a few tips for preventing blossom end rot in pots.

If your plants have already produced a few fruits with black cankers, it’s not too late to reverse this disorder for the rest of this growing season. Change your watering habits. Water deeply and less frequently. Remember, tomato vines need at least an inch of water every week, so if you don’t get enough rain, you’ll need to apply water from the hose or a sprinkler.

If you use a sprinkler, set an empty 1-inch-tall tuna can in the path of the sprinkler near the plants that have blossom end rot. When the can fills to the top with water, you’ve applied about an inch of water. Every sprinkler is different. Some will fill the tuna can in 40 minutes while others may need to run for 3 hours or more. Water in the morning whenever possible so the foliage dries before nightfall. Consistency is key. Don’t let the plants go through periods of drought, even if it’s just for a few days.

The existing cankers will not go away. Those fruits should be discarded. However, with proper watering and an added layer of mulch, new fruits will develop with no signs of rot through the rest of the growing season.

Though you may read or hear about blossom end rot remedies that involve antacids, crushed eggshells, and milk sprays, they are not viable solutions to this problem. Instead, focus on getting the calcium already present in your soil into the plants by watering them consistently. There are no “miracle fixes” for blossom end rot. The only time you should add calcium to your soil is if a soil test tells you there is a true deficiency.

For more on overcoming vegetable garden problems, please read the following articles:

Have you faced blossom end rot in your garden? Share your experience in the comment section below.