Estimated reading time: 22 minutes

This is the second part of a two-part series on creating and maintaining an organic vegetable garden. The focus of the first part was soil health and how to maintain healthy soil. In Part Two, we get down to the nitty-gritty of managing an organic garden and focus on the following topics:

From my writing desk, I have a perfect view of our backyard vegetable garden. Not a day goes by when I don’t think about the topics list above. Because a vegetable garden is so dynamic and ever-changing, these topics constantly come into play. With that, let’s start with Part Two of creating and maintaining an organic vegetable garden.

To understand and appreciate organic seed, we must first understand non-organic seed. Most home gardeners plant a seed for the resulting harvest and consumption of vegetables, fruit, herbs, and/or flowers. However, on seed farms, farmers cultivate plants specifically for seed production instead of edible food products. On non-organic farms, synthetic chemicals and pesticides are used on the plants that produce the seed. Not only that but current regulations allow higher percentages of chemicals to be applied on plants that are grown for seed production as opposed to consumption. Because plants being grown for seed are in the ground longer, therefore, more chemicals applied.

On the other hand, organic seed farms with a certification from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) must abide by the regulations of the National Organic Program (NOP). We know from Part One, that synthetic chemicals and pesticides are not allowed under this program. In addition, organic farms must use organic seeds to meet the requirements under the USDA National Organic Program.

Ok, so what does this all mean? Well, by choosing organic seed you are not contributing to pollution caused by conventional seed production due to the use of chemicals. In addition, you are starting your plants from seeds that do not have any chemical treatment. Therefore, a key to creating and maintaining an organic garden is the use of organic seed.

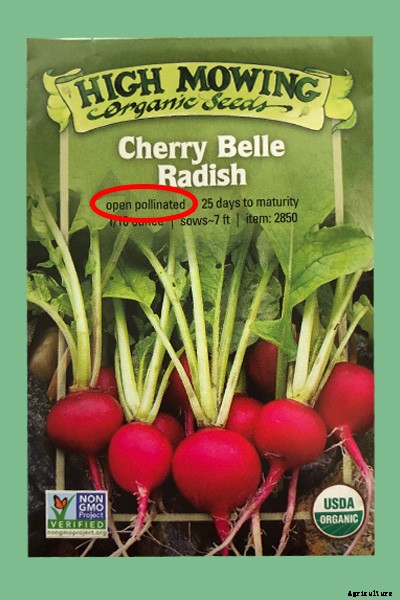

To complete our discussion on seed, we need to understand the various descriptors found on seed packages. Because these descriptions can be confusing, a definition of common terms can be found below.

Open-pollinated refers to plants that have been pollinated naturally by wind, insects, birds, or human hands. Since there is no restriction on the flow of pollen, open-pollinated varieties are more genetically diverse and can also adapt better to local growing conditions.

Open-pollinated plants will remain consistent from year to year as long as pollen is not shared between different varieties of the same species (e.g. between a Brandywine tomato and a San Marzano tomato). There are multiple benefits of open-pollinated seeds including: (1) the ability to save seeds, (2) seeds are less costly, and (3) the resulting food usually has better flavor.

With hybrid seeds, pollination is controlled by human intervention. When the pollen of two different species or varieties is cross-pollinated a new hybrid variety is a result. When an ‘F1’ label appears on a hybrid seed package, it’s the first cross-pollination of two species or varieties. These types of seeds take advantage of a specific trait or traits (such as high yield, disease resistance, better color, or taste).

Because hybrid seeds are genetically unstable, they cannot be saved for use in future years. In addition, the plants would not be true to the initial seeds. Also, hybrid seeds are not the same as genetically modified (GMO) seeds. GMO seeds have changes introduced into their DNA using the methods of genetic engineering as opposed to traditional cross-breeding as in a hybrid.

Seeds. of a specific cultivated variety, that have been around for more than 50 years (1951 and prior) are heirloom seeds. Think of them as an antique that was handed down through generations of gardeners/farmers. Heirloom varieties are open-pollinated which means that the plants have been pollinated naturally by wind, insects, birds, or human hands.

When you save seeds from open-pollinated varieties, they will generally produce plants mostly identical to their parents. In addition, heirloom varieties provide an important benefit by preserving biodiversity (variability among living organisms) within our ecosystem. Genetically modified seeds cannot be considered heirlooms.

Seeds that originate from plants where the grower is certified in the practices defined by the organic standards of a country can be labeled Organic. In the US, the governing body is the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Organic Program’s rules and specifications. Practices on organic farms include the reuse of resources, preserving biodiversity, and prohibit the use of chemical fertilizers. Organic seeds can be open-pollinated, hybrid or heirloom.

Biodynamic seeds meet the organic requirements for certification under the USDA National Organic Program and go further with “stricter requirements around imported fertility, greater emphasis on on-farm solutions for disease, pest, and weed control, and in-depth specifications around water conservation and biodiversity”.

Demeter USA is the only certifier for Biodynamic farms and products in America. In the picture at the left, the Demeter symbol is on the bottom left of the seed packet. Remember, seeds certified as biodynamic are also Organic even though the USDA Organic symbol is not present.

Tillage has been such a confusing topic for me personally. As I read about home gardeners adhering to no-till practices, I wonder what this really means. This section will discuss tilling practices that are good for soil health in creating and maintaining an organic vegetable garden.

First, let me start by saying I like the term ‘low till’ as opposed to ‘no till’. If you follow the soil health practices in Part One, there will always be a need to incorporate manures, compost, and cover crops into the soil via some low till method.

Now, let’s back up and define tillage and degrees of tillage in the context of a home garden. When applied in an agricultural sense, tillage is the process of agitating the soil by some mechanical means. Mechanical can be via hand tools such as broadforks, rakes, hoeing, or shoveling. In addition, there are methods such as rototilling and plowing.

What is the impact of tillage on soil health? Well, the soil is filled with a dynamic array of microorganisms that include both bacteria and fungi. Among other things, these microorganisms control plant nutrient availability, nitrogen cycling, and organic matter decomposition. Too much tillage can weaken the ability of these microorganisms to do their work. The bottom line, your soil will be more productive the less we disturb these microorganisms. Therefore, no or low tillage is better for soil health.

In conventional tillage, there are three types:

In the past, primary tillage was a common method for creating new in-ground garden beds. Today, there are no-till practices such as ‘lasagna gardening’ that eliminates the need for primary tillage. Lasagna gardening is a no-dig method to create a new garden bed.

This method, also known as sheet composting, is a method where the soil is left undisturbed under layers of mulch. Lasagna gardening takes time because the composting process is slow. Thus, give yourself time to plan. For our ‘lasagna’ garden beds, the process began in the fall and was complete the following spring. First, we marked out the area for the new beds. Next, a layer of cardboard was laid directly over the grass. From there we spread peat moss, composted cow manure, topsoil, and a layer of wood chips. In the spring, we had an amazing garden bed into which we directly planted.

The key to maintaining a no-till or low till garden is to cover the soil at all times. This includes planting your primary crops, using cover crops, or covering the soil with organic mulch such as leaves or straw. Tilling is also dependent upon the type of soil you have. It is generally easier to apply a low till method to sandy soils than to clay soils.

Our vegetable garden in NJ has heavy clay soil. While I practice cover cropping, I still find it helpful to perform primary tillage using a broadfork once a year. I use the broadfork to aerate and loosen the first 6 inches of soil prior to creating a smooth garden bed. For our soil, this process improves drainage, increases root depth, thus making nutrients more accessible to the roots.

At the end of the day, do what is best for your garden and soil type. Studies have shown that a less tilled garden is better for both allowing microorganisms to do their work and for sequestering carbon in the soil. For new garden beds, I highly encourage the lasagna method.

Irrigation is a universal topic whether you are creating and maintaining an organic vegetable garden or conventional garden. I cover it here because it is important. Have you ever stopped to think about what watering the garden accomplishes? We know plants need water, but why? Here is what watering does for plants:

So, what impacts watering frequency? Well, there are several factors including:

A general rule to follow is that sandy soils need ½ inch of water a week while clay soils need 1 inch of water per week. However, I find it difficult to think of watering in terms of inches. Therefore, let’s convert inches to gallons. We will use my garden as an example.

360 (Sq ft of my garden)/100 = 3.6 * 62 = 223.2 gallons of water/week

Now you know how much water you need for your garden. The next question is how long to run the water supply?

In this example, we will assume hand watering with a garden hose.

In this example, we will assume watering with drip irrigation.

Below are watering guidelines:

The approach for managing plant nutrients in creating and maintaining an organic vegetable garden is different from a conventional garden. In an organic garden, the strategy is to build nutrient-rich soil via adding organic matter such as composted manure, compost, and cover crops. In Part One of creating and maintaining an organic garden, the topic of soil health is discussed in depth.

However, even in an organic garden, it is usually necessary to supply supplemental nutrients. Plants need both macro and micronutrients. Good soil should contain the following three macro elements:

Fertilizers contain three numbers on the label such as 5-10-5. This implies the percentage of N, P, and K. In a 5-10-5 fertilizer, there is 5% nitrogen, 10% phosphorus and 5% potassium. A soil test will let you know whether your soil is deficient in any of the above nutrients except nitrogen. Soil tests cannot measure nitrogen because it is too dynamic.

Here are types of organic fertilizers that contain macro nutrients:

Calcium and magnesium are considered micronutrients. The difference between macro and micronutrients is that plants need higher quantities of macro nutrients while needing only minute supplies of micronutrients.

Each vegetable crop is different regarding nutrient requirements. In addition, nutrient needs change as the plant grows. While nitrogen may be needed to encourage new growth, when a plant produces fruit, phosphorous may be needed. Therefore, it’s best to research each crop to understand the nutrient needs.

I have come to learn that prevention and growing healthy plants is the best approach to managing pests in creating and maintaining an organic vegetable garden. There is a worldwide standard for managing garden pests (including disease) called Integrated Pest Management (IPM). I like the framework because it guides you through a thoughtful process to understand the underlying cause. Finally, the goal is not to eliminate all pests, but rather to manage pests at an acceptable level.

One aspect of IPM is prevention. There are two key practices you can follow:

Here are four options to manage pests in the garden. When considering options, chemical (organic or synthetic) should always be the last option.

Physical control involves preventing access to your plant or physically removing pests from the plant. Examples include:

Each year, there are more varieties of plants that are bred to be resistant to certain pests and diseases. When purchasing seeds, check the label to understand if the seeds are resistant to pests or diseases. Disease resistent varieties are usually hybrid seeds.

Sometimes you will read about attracting ‘beneficial’ insects to your garden. A few examples of beneficial insects include ladybugs (feed on aphids and spider mites), dragonflies (feed on mosquitoes and flies), praying mantis (feed on flies and grasshoppers), and parasitic wasps (feed on aphids, flies, caterpillars). To attract beneficial insects, plant native plants in and around your garden.

This should be your last option. However, there are organic chemical controls to consider. First, identify the pest. Second, determine the extent of the pest damage. Chemical controls should only be used when there is a pest problem that cannot be controlled with other methods. When resorting to chemical control, thoroughly read the label on the product. The label will indicate insects that are controlled, the proper application technique, the application rate/amount, and the toxicity.

Look for the Organic Label or OMRI label on any chemical control that you purchase for your organic garden. In addition, always read the label for directions on when and how much to apply.

As is the case for pest management, the key to disease management in creating and maintaining an organic vegetable garden is prevention. Use the following strategies to manage disease in an organic vegetable garden.

There are many hybrid plants that have been specifically bred to resist disease. This does not necessarily mean that the plant will not get the disease, but the impact will not be as great. Seed packages will list the disease resistance.

Crop rotation is the practice of moving vegetables around your garden each year (e.g., not planting your lettuce in the same place each year). Why is this important? Rotating crops does two key things, first it interrupts the insect and disease cycle that may have disturbed your vegetables in the prior year and second it allows the soil to regenerate from the nutrients that the prior crop took out of the soil.

Air circulation and light intensity are improved with proper spacing, thus discouraging disease from developing.

If left in the garden, additional plants can be impacted by the same disease.

Because drip irrigation concentrates water at the base of the plant (instead of the leaves), disease is less likely to occur.

Mulching will control disease by reducing contact between the plant and soil. Mulches include straw, hay, wood chips, and leaves.

Clean up old plant debris and sanitize garden tools and contains after use.

Organic fungicides can be helpful to prevent the development of disease. Thus, apply fungicides prior to evidence of disease. Here is a link to a good resource for more information about organic fungicides. Look for the Organic Label or OMRI label on any chemical control that you purchase for your organic garden.